Underwater Aircraft Archaeology Researcher and PhD Candidate

Dominic Bush joined Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum for as the featured guest of Sunken Treasures: Underwater Aircraft Archaeology — a live webinar to discuss the fascinating science and law behind the preservation, conservation, and documentation of historic underwater aircraft sites.

Dominic Bush grew up in Kailua, Oahu, just two minutes to the nearest beach. Bush filled his time with snorkeling and diving off the coasts of Hawaii. As he grew up, he became passionate about the history of Hawaii and WWII, and how the two truly are very intertwined. This passion led him to study the “little oasis” that can be present at underwater aircraft wrecks.

Below is a Q&A with Dominic including questions not answered live and a few key moments in the webinar you don’t want to miss!

#1: How long does the entire process of uncovering an underwater aircraft wreck roughly take?

A: The simplest answer is that it is a matter of funding. Without money to support research and fieldwork, it is impossible to plan and execute a project. It may take months or years to secure funding, often in the form of grants, which involves a cycle (or more) of applying. If funding is obtained, as we did with a National Center for Preservation Technology and Training grant (National Park Service), then one can start, or more often continue from research completed as part of the grant application process. The archival/background research can take longer or shorter based on the availability of information, the type of aircraft, its location (whether it is known or not), and its completeness.

With respect to permitting in Hawaii, all archaeological work must have an Authorization to Conduct Archology granted by the State Division of Historic Preservation. In my experiences, the SDHP is really on top of things, and permits are granted within a short turnaround time (less than 2 weeks) from the time of application. Additional permits from NOAA (if the site is in a National Marine Sanctuary, e.g. Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale NMS) or the Naval History and Heritage Command (if work will disturb a naval aircraft wreck) may also be required depending on site location and aircraft type.

My favorite part, collecting data, whether its archaeological measurements, photographic, biological, etc., is also the shortest part. On Maui and Oahu, we spend only 2 days diving (less than 4+ hours each day) on each island. Although the shortest when measured by length of time, it is often the most expensive part, due to travel costs, boat costs, and SCUBA/other equipment rentals. There is a general rule that for every hour spent in the field collecting data, another 3 hours are required in the laboratory/office processing and analyzing data. This could take anywhere from a few days to over a year depending on the data interpretation methods (e.g. DNA analysis).

#2: Have you had much success finding aircraft through charts or navigational records, or has your research been led by some other means?

Dominic and colleagues on research boat.

Dominic and colleagues on research boat.

Dominic and colleagues on research boat.

Dominic and colleagues on research boat.

A: For my specific research, I focused on sites that had been previously known and were a part of the Submerged Cultural Resource Inventory completed for BOEM by NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program. However, while planning for future projects, especially in remote locales as is often the case with WWII in the Pacific, I have relied heavily on a combination of archival records, especially ship logs, and navigational charts to figure out what is possibly out there and which areas would be best for an archaeological survey.

Webinar: Dominic compared looking for an aircraft wreck to “looking for a needle in almost an infinite haystack.” Because of this, Dominic believes the best method is to discuss with local divers who are comfortable and knowledgeable of the waters in the area. According to Dominic, most sites in Hawaii have been discovered and confirmed by local divers. Discussed at 21:00.

#3: What is the best identifier for submerged aircrafts to determine identity?

Dominic collecting the exact samples from the site as permitted by the U.S. Navy.

Dominic collecting the exact samples from the site as permitted by the U.S. Navy.

Dominic collecting the exact samples from the site as permitted by the U.S. Navy.

Dominic collecting the exact samples from the site as permitted by the U.S. Navy.

A: The single best identifier is a planes bureau number (for naval aircraft) or its serial number (for army aircraft). This unique number is often painted on either the tail assembly or the rear of the fuselage. The engine also has a data plate inscription that can be used to identify a specific aircraft. If the identifier numbers or engine plate are missing, which is often the case, then one can begin to look at diagnostic features of the aircraft, starting with overall shape, tail assembly, and canopy/wing structure. More specific features, such as a plane armament, landing gear configuration, engine components, exhaust flaps, and ancillary parts (e.g. floats of a seaplane) can also be used to narrow down to a wreck to a specific make and model. The physical information about a plane, including which model of aircraft it is and its condition, can then be compared with archival information about wrecks in a certain area and details of crash reports to make inferences on the plane’s exact identity.

Webinar: Dominic discusses the tragedies linked to all aircraft wreck sites and how researchers search the plane for even the most minute signs of human remains at 19:15.

#4: Do you recover or remove anything from an aircraft to study when it is discovered?

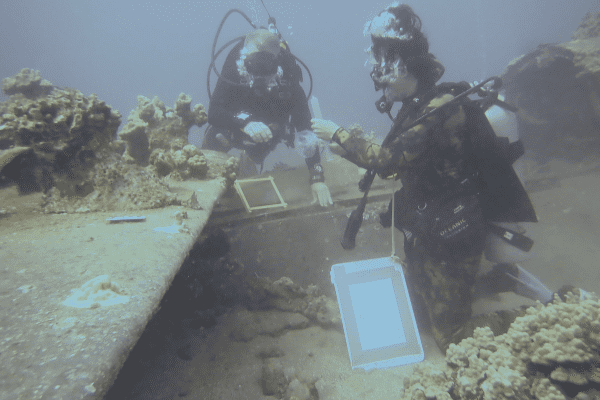

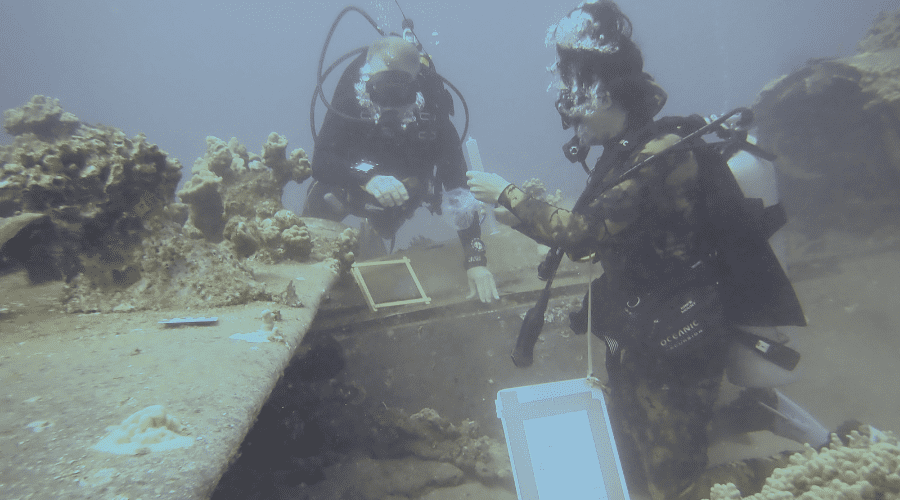

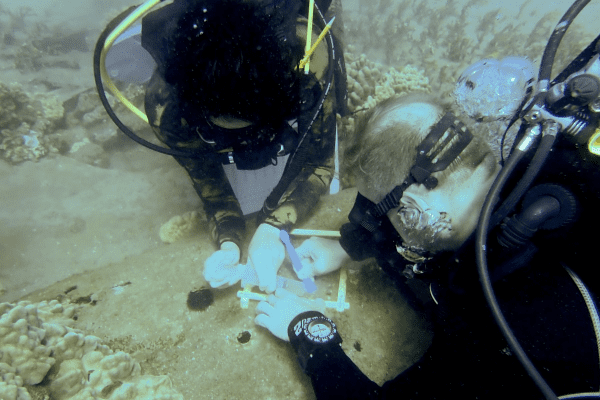

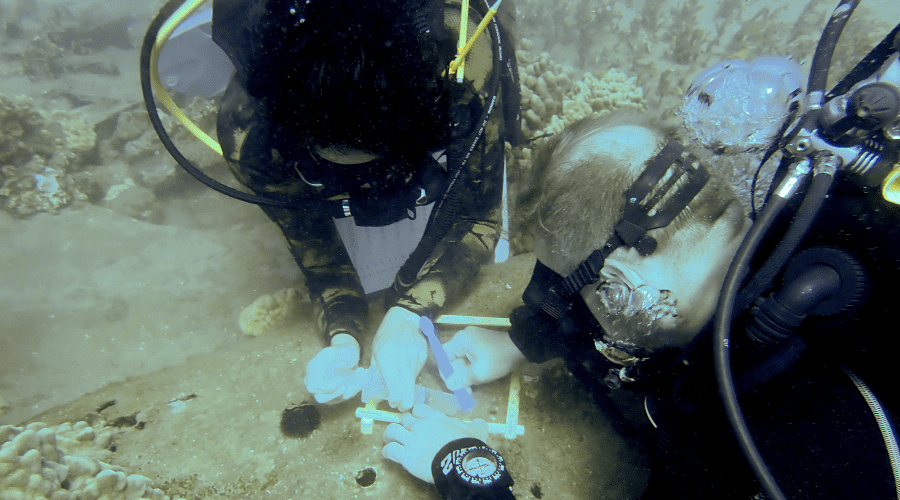

Dominic and his colleague collecting microbial data from an aircraft wreck.

Dominic and his colleague collecting microbial data from an aircraft wreck.

Dominic and his colleague collecting microbial data from an aircraft wreck.

Dominic and his colleague collecting microbial data from an aircraft wreck.

A: Given that my research is focused on situation preservation of aircraft, I do not recover artifacts from planes and only take biological samples for testing. The decision to recover artifacts, as opposed to the entire plane, should adhere to the same logic as above. It is really a matter of being able to conserve the object once it is recovered and the rationale behind wanting to recover it, as removing it alters the site forever. I would advise against recovering anything from planes (with the exception of sanctioned-human remain recoveries or requests from a victim’s family) associated with the loss of life, as it is akin to grave-robbing.

Webinar: Dominic discussed the specific details of his data collection, including measurements, photographs, videos, biological samples, and more at 29:45.

#6: Who owns the aircraft and are there any laws to protect and preserve these historic sites?

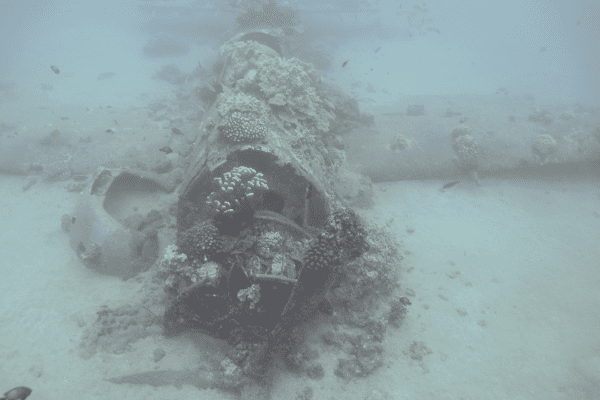

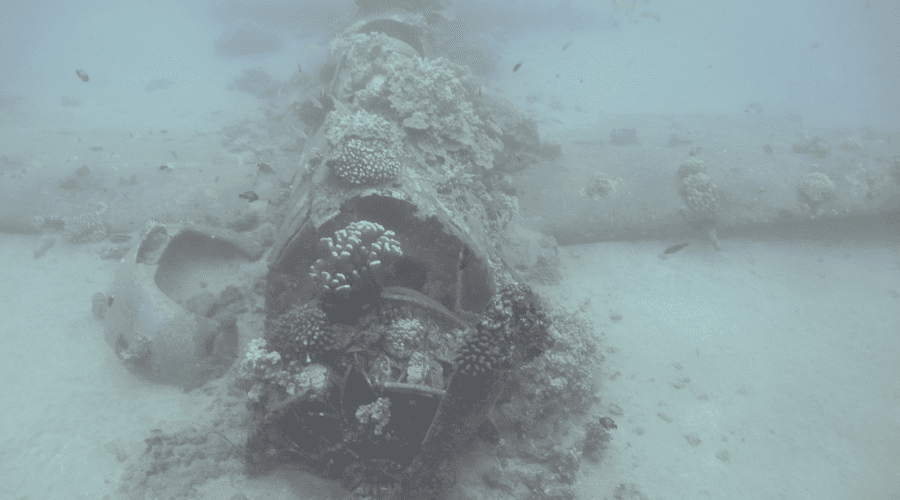

Helldiver aircraft wreck

Helldiver aircraft wreck

Helldiver aircraft wreck

Helldiver aircraft wreck

A: The U.S. Constitution’s Property Clause in Article IV establishes Congress’ perpetual right, title, and ownership of materials produced for the U.S. federal government (including the military), which can only be extinguished by express written consent. Congress, through the passing of legislation (i.e. the Sunken Military Craft Act), has allowed the individual military branches to manage their downed aircraft, with the U.S. Army abandoning title to all pre-1961 aircraft.

To recover or otherwise disturb these aircraft, it is still necessary to get the permission of the landowner (an agency/department in the case of state and federal lands). For Naval aircraft, permissions to recover or perform any archaeological work that may affect an aircraft is up to the Naval History and Heritage Command.

For both army and naval planes, they may also be protected under the National Historic Preservation Act. This law mandates that any kind of work that involves the federal government requires that all historic resources in the area of a project need to assess the likelihood that the work will affect said resources. In this case, resources are evaluated by a criteria that is used to determine their eligibility for the National Register of Historic Planes. Most WWII aircraft would meet the criteria, and projects that would affect them would need to have a plan outlining the effects and mitigation plan to satisfy the regulations put forth by Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

To supplement the federal level of protection, many states have passed their own historic preservation laws that may require additional permitting to work/recover historical resources such as WWII aircraft.

Webinar: Dominic discusses the Sunken Military Aircraft Act at 14:35.

#7: How do you decide when to document vs. when to recover?

Dominic documenting collections and data while diving on a wreck site.

Dominic documenting collections and data while diving on a wreck site.

A: Personally, I believe the issue of documentation and leaving in situation vs. recovery should be on a case-by-case basis. Wrecks that are associated with the loss of human life or serve as popular recreational (e.g. SCUBA or snorkeling) sites should not be recovered given the cultural and socio-economic value, respectively. Instead, efforts should be focused on how to best manage these types of sites from a human and natural (e.g. corrosion) perspective. Recovery is more appropriate for non-war grave wrecks that were lost in areas that are generally inaccessible to the public.

The Lake Michigan planes represent one such possible example, though even applying a blanket statement such as “recover all Great Lakes aircraft” is problematic and should be avoided. Recovery also must account for conservation efforts following the raising of a wreck. If the entity interested in recovering an aircraft lacks the appropriate funds and facilities to properly treat a formerly-submerged plane, then recovery should be postponed until the situation is rectified. Otherwise, the aircraft can suffer irreversible damage that could have been avoided if the plane had been left in the water. As of now, archaeologists are still unsure of the long-term (100+ years) sustainability of aircraft in aquatic environments, as we do not have case studies similar to iron/wooden shipwrecks that have been in the water for centuries. In general, it is probably best to not recover, except in very specific situations, as our knowledge of the decay processes affecting submerged plane wrecks is still very much evolving.

Additional Questions Submitted for Sunken Treasures Webinar

Under what condition are groups able to salvage historic sunken aircraft from historic battles? Thinking of this question in relation to the recently discovered USS Lexington CV-2 wreck and the Japanese aircraft in a Truk lagoon.A: While the preservation of the Lexington aircraft is superb, the depth makes it a logistical nightmare and near impossibility that it will be recovered. The Helldiver recovered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers off Cape Cod cost 2 million dollars and was in 14 feet of water. Ten thousand feet below the surface is a much different situation. Then there is the issue of the Lexington being a war grave. Personally, I would feel uncomfortable disturbing the ship in any meaningful way, even if it is to retrieve (if it were physically possible) the aircraft.

The Japanese aircraft are outside of U.S. jurisdiction even if the wrecks are within U.S. waters or waters of a host nation that the U.S. has an agreement with (e.g. Federated States of Micronesia in the case of Chuuk). This is in part due to the Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004, which granted protections for U.S. military craft in U.S. and international waters, with the same right being extended to foreign military craft found in U.S. waters. Other international agreements, especially those fostered through the United Nations, have confirmed individual nation’s sovereignty over their submerged war material. Given Japan’s overall feelings towards WWII, it is extremely unlikely the Chuuk aircraft or any other Japanese WWII planes will be recovered.

Webinar: Other historic shipwrecks, such as the USS Yorktown and Titanic were discussed at 54:35.

What do you think got Paul Allen into the businss of searching for sunken Navy ships?A: Outside of a genuine appreciation for U.S. military history, I believe I read somewhere that Paul Allen’s father served in the Army in some capacity. Whatever the reason, I sure am happy he had that interest and his passing was a sad one.

Were there more aircraft discovered/recovered underwater in the Pacific or European theater?A: I am not aware of any exact totals for either theatre, with respect to the aircraft that have been discovered or recovered. In general, aircraft that have sunken in saltwater make poor candidates for recovery giving the issue of conserving metallic object from salty environments (though some aircraft, especially in Europe near the English Channel, have been raised from the sea). Wrecks on land, more so in Europe than the Pacific due to the differences in populations, were largely scavenged by enthusiasts and amateur archaeologists following the war, when WWII aircraft were not yet viewed as historical resources. This makes planes wrecked in freshwater the best and most likely candidates for recovery. While some have been fished out of European lakes, the Great Lakes are perhaps the most fertile grounds for recovery due to their use as carrier operation training grounds during the war.

In terms of discovery, I believe the total number of army planes lost in Europe/Mediterranean was around 27,000 and in the Pacific it was between 12,000-13,000. I would assume it would be a similar split for naval aircraft (those stats are not readily available), though I suppose there could relatively more naval wrecks in the Pacific given the reliance on the Marines and Navy for the island-hopping campaigns. It should be noted that 21,000 planes were lost in the U.S., mainly to training accidents.

Webinar: Dominic discusses the number of underwater aircraft wreck sites surrounding the Hawaiian Islands, and the training the lead to them at 5:16.

Watch Full Webinar: Sunken Treasures: UNderwater Aircraft Archaeology with Dominic Bush